Daniel Coburn first discovered 19th century alternative photographic processes as an undergraduate studying under the accomplished alternative process photographer Marydorsey Wanless. Although he has recently come to be known for his work with the cyanotype process, Daniel has worked in the full range of alternative processes. He says it’s not about the process; it’s about choosing the right process for the project.

For his master’s thesis, completed at the University of New Mexico, as well as for his series Domestic Reliquary, Daniel used the salted paper process. The work in his new book, The Hereditary Estate, was created using a 100-year-old large format camera. “The cyanotype process is one of my specialties, but my total body of work is really quite eclectic,” he says.

The modern cyanotype process is also known as Ware’s. “I started to seriously pursue the cyanotype process three years ago in my own artistic practice. I created a body of work called Waiting for Rapture, as I worked to perfect that process,” says Daniel.

“Depending on the project I’m working on, I use the tools and the processes that are correct for the concepts or imagery that I’m making.”

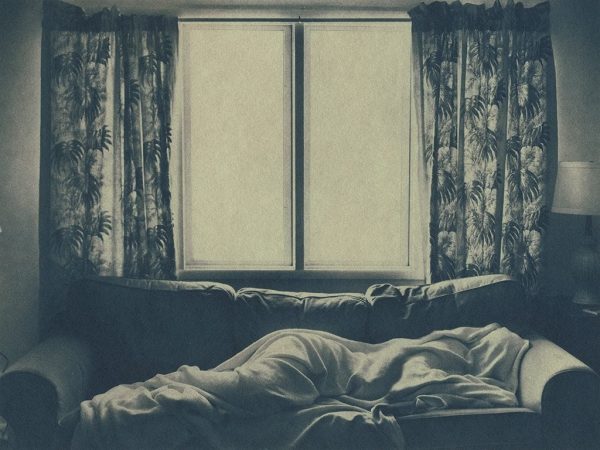

Much of Daniel’s work, like Waiting for Rapture, is closely linked to memory and documentation. “I’m very interested in the conceptual link of the history of the process that I’m using and how it ties to the subject matter of my photographs.”

Cyanotype prints are actually regenerative. While the image will fade over time, if stored in cool, dark place for a certain amount of time, the image will regain contrast. It’s interesting to note that the work of the English botanist and photographer Anna Atkins is often displayed in museums under a black cloth for this reason.

“I’m interested in how the restorative quality of the cyanotype image relates to memory,” says Daniel. “My work is all about family and memory. The cyanotype’s ability to recover from the affects of time and exposure to the elements, is an interesting link to the imagery that I make.”

The cyanotype process was employed by scientists in the 19th century to document botanical specimens. “Because cyanotypes were used in the service of evidence, I make images using this process to elaborate on the true nature of family,” he says.

As an art form, photography has a relatively short, but very well documented history. Daniel says he finds value in that, and also in the fact that modern technology allows us to engage with some of the oldest photographic processes in a new way. “I’m not a purist—I’m really interested in the intersection of the latest technology and the oldest technology. Digital technology gives us the capacity to really perfect the images made with these early processes.”

On the other hand, combining digital processes with traditional, hand-made techniques often makes photographic prints more desirable by collectors. “Even when you use a digital negative, you’re still making a one-of-a-kind object. Each photograph that I make, regardless if it’s made with a digital negative or not, is a unique object,” says Daniel. “It’s a much more intimate experience to look at an image that’s been created by hand, rather than what you get with an image that’s been created completely digitally.”

Daniel says that photography is not only about creating an image, but also about choosing the correct materials to communicate your ideas. This includes paper choice, and the process you decide to use. “To me photography is about visual communication, and if you can somehow link the imagery you’re making to the materials and the process, your prints become more valuable and rich.”

His work has recently been featured in the International New York Times, The Diffusion Annual, and Black and White Magazine, and he teaches a course in alternative process photography at the University of Kansas, where he is an Assistant Professor.

In May, Daniel will teach a three-day workshop at The Image Flow. He will present the cyanotype process, but also teach participants how to use toning techniques to create a wide range of color tones. “It’s a common misconception that cyanotype images are all cobalt blue. The process is very versatile. You can use various household substances like detergent, red wine, coffee, and tea, to tone the image, with results ranging from yellow to black,” he says.

No alternative process experience is necessary, and this workshop is well suited to all levels of photographers. It is not a digital negative class. Participants will use a set of pre-made curves to achieve the maximum tonal range needed for the cyanotype process. All materials are provided and you will print digital negatives from you own photographs during the workshop.

“This is a very experimental process. Having a basic understanding of Photoshop is suggested, but you can also bring in found objects, drawings made on transparency, anything opaque that you want to place on the paper,” says Daniel.

“Everybody brings their own experience to the table. I love this workshop because we’re all working together, learning from each other and our mistakes.”

Learn more about Daniel Coburn’s three-day workshop at The Image Flow, May 15 – 17.