Of all the eras and styles in the medium’s history, art historian and photographer Jeffrey Martz is most drawn to the 19th-century amateur pictorial photographers such as Lewis Carroll, Clementina (Lady Hawarden), and Julia Margaret Cameron.

“An amateur photographer was a clearly-defined category of maker in the 19th century, someone who pursued photography seriously but not professionally. They weren’t in a studio trying to please a client, and because of this, they were free to make the best possible pictures in whatever style they wished. They did their work literally for the Latin root of the word—am—or love,” Jeffrey explained.

He earned his MFA in Photography at Utah State University in 1997, and he has been the photography teacher at Sir Francis Drake High School for the past 20 years. He regularly gives talks at The Image Flow and elsewhere in the community on the history of photography, from the daguerreotype to digital.

“As a photographer working to create something special, the onus is on me to create something rare and worth my viewer’s attention; to create something that cuts through the glut,” he mused. “Otherwise why put anything on the wall?”

Jeffrey works in a wide variety of techniques, from pinhole photography to topographic photography to large-format black-and-white photography created with a view camera. Regardless of where or with what he’s shooting, he approaches his work with the spirit of play in mind.

“Spending most of my time with the history of photography, it’s easy to become burdened by the medium. When I’m out there with a 5×7 view camera I have Paul Strand on my back, Edward Weston, Eugene Atget, I have all these people that have come before. It’s like having a chorus of little devils sitting on my shoulder saying, ‘It’s not as good as ours.’”

His latest body of work, Faster but Slower, was born during a car trip through Oregon’s Willamette Valley. He initially made the images as an experiment with shutter speed and movement, exploring with his camera in a lighthearted way. He didn’t expect much from the images and didn’t look at them for a few weeks.

“I’ve always made my best strides as an artist photographer when I’m at play and not caring about the outcome. This body of work came from a decision to photograph a moving landscape in a counterintuitive way. When I finally looked through the images, I was floored. I immediately knew that the work was excellent and, like all the greatest moments of grace in my life, I just began to laugh,” he recalled.

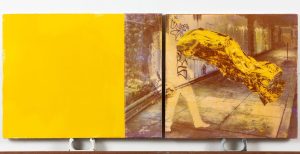

The images, a combination of motion blur and moments of extreme sharpness, are something akin to a Post-Impressionist painting. Jeffrey went on to photograph some 20,000 more images over the next several months working to refine the technique.

“I’m extraordinarily excited the way I’m creating this work, but the failure rate is enormous. I’ve never failed as much as I have in the past year. For every 400 to 500 photographs I take, I will maybe have one that is successful.”

Jeffrey will show approximately 27 images from the portfolio in a new exhibition at The Image Flow opening February 17th. The color images will be printed poster-sized, up to 50 inches across.

Panning and blurring, either through motion or shallow depth of field, are often used to create pictorial photographs, but what’s interesting about Jeffrey’s work is that the streaks of motion created run in several different directions while other sections of the image are in sharp focus. This formal pictorial vocabulary challenges the viewer to suppose how the work was even created.

Photography has been in a constant state of evolution from the moment Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre made his first images. Today, we don’t have to confine ourselves to the darkroom trying to perfect the high dynamic range photograph à la Ansel Adams; we can do it on our iPhone. Professional photographers make a living from it—and a sometimes a good one—but others, like Jeffrey, still recall those early pictorial photographers.

“I am absolutely an amateur, and I will be one for the rest of my life. I make photography out of the 19th-century spirit of love with a healthy dose of play. I’m only interested in the artistic impulse, the amateur spirit, and the joy of discovery with the medium.”