Here at The Image Flow, we have some pretty amazing clients that we work with on a regular basis. From artists and educators to humanitarians and scientists, people come to us from many different paths, all connected by a love for photography. In an effort to share some of these clients’ inspiring stories and backgrounds, we’ve started to interview some of these fascinating people to help spread their stories and inspirations.

In this interview, Lori Barra speaks about her work as a humanitarian, her mentor Mary Ellen Mark, and the importance of connecting with your photography subject.

Well, my day job is really a second career. My first career was as a graphic designer for thirty years; I had my own studio and I designed books. I started in the magazine world, I was an art director and designer. I designed magazines in New York for years and then I moved here and worked for Apple as an art director.

Then, about twelve years ago, I got this offer from Isabel Allende, my mother-in-law, to run her family foundation. I was very hesitant at first because I didn’t know what I’d do without design, I just lived and breathed it all the time. So I started doing both and what happened was I then went from having a six day a week job to having two five-day a week jobs and it was just too much work. After about a year I had to make a choice.

I went to her to say, “I can’t give up design, this is really important, this is my heart and soul,” but when I sat down with her, without thinking about it I said, “I think this foundation work is really important, I’m going to do it.” So I let go of my design business at that point, and for the last twelve years, I’ve been primarily dedicated to my work for the foundation.

But in the background, I had majored in design and photography, but I knew early on that I never wanted to be a professional photographer because that required taking pictures that other people wanted you to take. Photography had always been far too personal an act for me, it was about my soul and my heart, whereas design I could be more collaborative. But with photography, it’s a very quiet space for me.

When I started doing the foundation work, it felt like my blood wasn’t flowing, I didn’t know what to do if I wasn’t dealing with texture and color and design and fonts. So I started doing photography again, which I’d always done a little bit. But then I had this amazing encounter on a vacation where I ran into Mary Ellen Mark on the street and nearly threw myself at her feet and said, “oh my god, I can’t believe you’re Mary Ellen Mark, you’re my hero,” and she invited me to a workshop.

She called and told me she’d really like me to come to her class in Oaxaca, and I ended up studying with her for seven years in a row until she passed away. We became very close friends, and she also became friends with Isabel as well.

To keep myself attached to what’s really important, I photograph. It doesn’t always matter to me what the photograph looks like because the photograph is done once I’ve taken it. The part that’s really important to me is to photograph people that I feel connected to.

Well, there is because once I started photographing in Oaxaca, I connected with people who were first photographic subjects and would later become significant to the Isabel Allende foundation’s mission.

Mary Ellen was just as brilliant a teacher as well as a brilliant photographer. There was a range of people in her classes; some people would come in with prints that had just been in a gallery in Soho, and then there were people who would come in with their drugstore prints and say, “I really feel attached to this but I haven’t done much yet.” And she would take each person and somehow reach into their inner being and pull out the best of you.

The first day, she would look at your portfolio in front of everyone and she would say “This is what I think you should be doing here” and she gave people assignments. She said to me, “I think you need to photograph children.” She sent me to the orphanages and the schools for the disabled kids, and I just fell in love with them. I worked there many years in a row, and by the fourth year, I started to realize that these were groups that fit into the mission of our foundation. The foundation’s mission is about empowering women and girls, and so I brought some of these children in as our grantees.

So now when I go to these places, I have a dual role which is to do a site visit and see how they’re doing, but also to photograph.

Yeah, it’s a gift, it was really a gift from Mary Ellen and a gift from the gods, it was just the perfect scenario. You know, when you’re doing what you love and you’re in that moment where nothing else really matters, that’s how I feel when I’m there. And I don’t always come away with great photographs, but I always come away with my heart having been touched.

I think it’s about self-discovery, when I photograph I learn so much about myself and the world in relation to people, in relation to things and experiences. I really love making connections. Sometimes I’ll go to the disabled children’s home and I’ll only take a handful of pictures but I’ll be there for six hours because we’re playing ball or we’re playing cards or I’m braiding their hair, or whatever it is, and that, to me, is so joyful, to be with these kids who are so pure of heart and so lovely to be with. Every bit of progress that they make is monumental to them.

Then when you come back the next day, because I always come back at the end of the week with little cheap pictures for them, they just go crazy because they’ve never had pictures of themselves. They don’t know what they look like in a photograph and they love it.

I try to make the effort to connect on a human level even before I start thinking about photographing. When I go to some of these places, I’ll just sit for the first day and just watch what’s going on. I’m much better in a quiet space when I’m photographing. I don’t mind the kids interacting but sometimes in group classes, for example, they’ll send several people out to the same place and that’s so distracting to me. I don’t want to pose anyone, I want to wait and see what happens. Sometimes you wait all day and nothing extraordinary happens, but then sometimes you get a moment that’s really lovely, and you just have to wait for it.

Kids are like cats; if you go after them they run away, but if you sit there, suddenly you have three of them on your lap, and they always want to play with the camera. I always let them take pictures, I show them how to do it, and everyone gets a turn.

Yes, I try to, and it’s an extraordinarily rich experience. The people that run these organizations are these incredible selfless people that could be doing a million other things but they’re not, they’re feeding, bathing, cleaning, and helping kids who don’t have a chance in Mexico because it’s survival of the fittest there.

For example, the Down syndrome school is this extraordinary place, and it was started by a woman who is a doctor and has three children; two of them are doctors and one of her children has Down syndrome. She found that she had no place to put her child during the day, no place that would be healthy, and a large majority of kids here that are disabled or have Down syndrome are left home all day alone locked in, or taped to a chair, just these incredibly brutal situations. You can’t even really blame the parents because if both of them aren’t out working then the other kids aren’t going to get fed either.

So she decided to start this organization by herself, and day by day people came, people heard about it through word of mouth. She doesn’t require much from them, I think she requires like fifty cents or some extraordinarily small amount of money per day, but she runs it for the most part all by herself. The expenses are high, and she gets therapists sometimes to come in and teach the kids for free or at a discount.

There are about twenty to thirty kids on and off, and they’re such good kids. The only thing they want is to be loved, and they’ll love you right back.

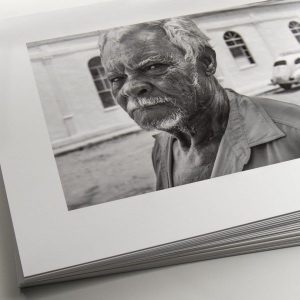

Photo ©Lori Barra

It’s odd but when I look at my photos I don’t think of it as a particular style I look at it and I think, “oh, that’s Alejandro and that’s Edu,” I guess if I had to name it it’s a kind of environmental portraiture, I think that’s what it is most. I don’t ever want to show or prove anything specific, it’s about the moment with each of the people I photograph. I would like to do more advocacy work, but I’m leery about making a point and telling people what they should think.

Photo ©Lori Barra

I would say that because of my background my photographs tend to be somewhat graphic. I’m very aware of composition and not having too many extraneous things contained within it. I try to make the images feel soft and warm, but I hope not too sentimental.

I guess more so than a visual aesthetic, I hope that in taking these pictures of what could appear to other people as incredibly disadvantaged kids that I don’t take anything away from them, but that I give them back the beauty that I see in them. That’s what I’m mostly thinking of when I take a photograph, is how beautiful they are and how I can show that to other people.

Photo ©Lori Barra

While I’m shooting, I’ve noticed that I’m really hyper-aware and focused, and I’m constantly looking to see what changes, because a beautiful child without beautiful light is not a photograph, and beautiful light without content is not a photograph either for me. So I’m always really focused on how to bring those things together.

After a day of shooting (because I’m usually there for between six to eight hours), I’m spent, just completely exhausted. And I go home and look at the photographs, and this is classic, I look at them and I think, “I didn’t get anything.” Then the next morning I look again and I think, “maybe there’s one or two.”

I look at the images about six times before I start to edit. Even though I want so much to go in and edit right then because it’s so fresh, I don’t have any distance until about a week later because I’m so emotionally attached to what I just experienced. Then I look back after a week and I can say “Yeah I love Edo, but that’s not a good photograph.” It has to be a photograph, up until then, it doesn’t matter that they’re photographs, it was an experience.

Yes, and oftentimes the one that I think is great right away is really just the fact that I love that kid. The kids that I’m most attached to, like these two twin girls that are deaf, I met them the first year I went and fell in love with them. I said to their mom, “can I follow you home?” and years later she told me she thought I was absolutely insane. She didn’t understand at first why I was so in love with her kids.

Long story short, we’re going to be padrinos at their quinceañera seven years later, but I have the hardest time capturing them, and I don’t know why. Because I love them so much, I just think every photo is really great, it’s like photographing your own kids, you know? So I have not gotten a truly great photo of them yet, and I’m waiting. I’m still working on it.

You know, I learned so much from Mary Ellen, so this is her channeling through me, but the one thing she always told me was “go back; go back,” you’re not going to get depth just by taking a quick shot of somebody on the corner. You have to go back, you have to make yourself a part of them, and they a part of you, even when it’s not working, you have to go back.

And I would say that if you have a chance to learn with a master there is nothing better. If you find somebody who is really your mentor, it’s worth putting yourself through whatever you have to do to do it because there is so much to be learned.